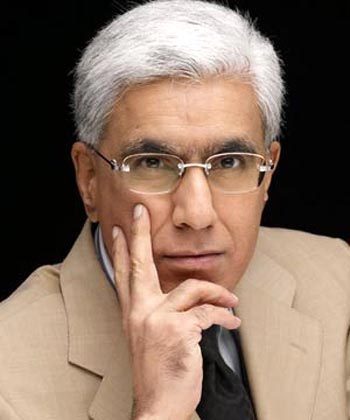

Israeli filmmaker Nadav Lapid (File photo)

New Delhi: Now that a little time has passed and passions have, hopefully, cooled I want to reflect on the furore surrounding Nadav Lapid’s critique of The Kashmir Files. I believe it reveals some disturbing, even, distressing facets of our society and, what you might call, our national character.

For a start, we invited one of the world’s most eminent film makers, a winner of the Special Jury Prize at Locarno and the Golden Bear at Berlin, to preside over the jury of our International Film Festival but couldn’t accept his honest criticism of an Indian film. As Lapid put it: “In a way it was my duty, my obligation. I was invited to be frank not to speak vanities.” That candour may have surprised and hurt us but we lacked the strength and moral fibre to cheerfully tolerate it.

Worse, we deliberately chose to misconstrue what Lapid said. He criticised a badly made film. Having deliberately chosen not to see it in March when it was released, I made a point of doing so after the controversy. I found it a crude portrayal of a tragic event that needed thoughtful and sensitive handling. The narrative lacks subtlety and depth, the acting is one-dimensional and there’s not a single character you empathise with. That’s what Lapid was saying but we wilfully misinterpreted his comments as denial of what happened to Kashmiri Pandits and an insult to the memory of the dead.

If we had paused to think for even a moment we’d have known how wrong we were. But we didn’t perhaps because this was the only way of defending a second-rate film. Once Lapid’s criticism had hurt our pride we resorted to deliberately distorting his critique and view it as an attack on our nationalism, indeed on ourselves. But as Lapid explained: “criticising a movie is not criticising India or criticising what happened in Kashmir.”

Let me, however, go one step further. We want the Goa Film festival to be recognised as one of the world’s best. If that is to happen we know we must scrupulously ensure the highest artistic and aesthetic quality of the films it features. So why was The Kashmir Files chosen? For its merit? Or because it appealed to the ideological bent of our government? Ensuring a window to the world for a tragedy that’s been ignored obliterated all consideration of the fact it’s both crudely and amateurishly portrayed and this movie does not show our film industry at its best.

This is how Lapid put it: “Movies like The Kashmir Files shouldn’t be part of the competition section at film festivals. I have been part of the jury at dozens of festivals, including the international ones held in Berlin, Cannes, Locarno and Venice. Never ever have I watched a movie like The Kashmir Files. When you show a movie like this to the jury, you force them to behave differently.” This is not an unconvincing argument.

Finally, let me come to the media. It claims to speak for us. It believes it’s the voice of the people. But its attempts to defend the film were unintelligent and ineffectual. When Lapid said “all the jury members shared exactly the same impression about the film” television anchors challenged him to prove it. This was a silly attempt to suggest he was lying. Instead, it provoked the other jurors to publicly confirm their support. On the other hand, one newspaper actually lied. It reported Lapid had changed his mind and called the film “brilliant”. He had not and it was foolish to claim he had.

I’ll end with a simple thought. Whether or not Lapid was right to criticise a specific film at the award ceremony is a legitimate question. But it is also a small matter. A far bigger concern was our behaviour. Both the film we deliberately chose and our response to the criticism it received has left us embarrassed. This was, therefore, a sad and sorry story. IANS

by Karan Thapar

by Karan Thapar