Until recently I only knew of two authors who’ve written about their parents’ marriages. One is Nigel Nicolson, who’s ‘Portrait of a Marriage’ was about the volatile but versatile relationship between Vita Sackville-West and Harold Nicolson. The other is Zareer Masani’s ‘And All Is Said: Memoir of a Home Divided’ about the rivalry, bitchiness and infidelities that separated Minoo Masani from his wife Shakuntala. She chose to join Indira Gandhi’s Congress (I) whilst Minoo was the official Leader of Opposition in the Lok Sabha. It was quite a cause celebre.

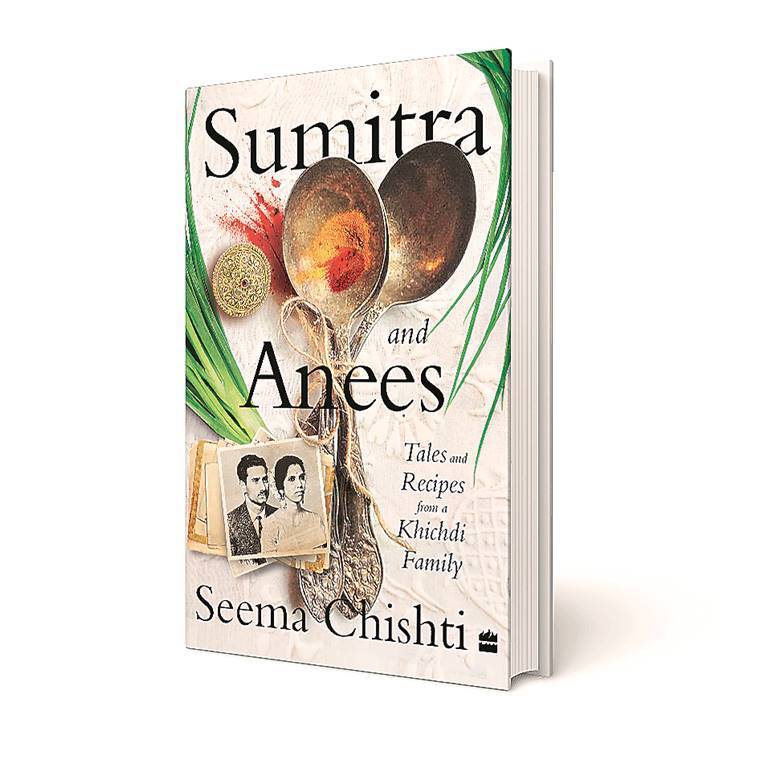

I’ve just read the third book. Called ‘Sumitra and Anees: Tales and Recipes from a Khichdi Family’, it’s the story of Seema Chishti’s parents and their unusual but, this time, deeply loving marriage. It’s refreshingly different.

I was drawn to this book because Seema, straight out of college, began her first job with me. So when the book arrived on my table I didn’t hesitate to pick it up. Sumitra and Anees’s marriage was, of course, unusual. She was a Kanadiga and a Hindu. He was from Deoria in UP and a Muslim. She was also seven years older. They got married without telling either family but, fortunately, were warmly accepted by both.

In telling their story, Seema has adopted an intriguing style. Sometimes she writes of them as “my mother” and “my father” but a lot of the time she does so in the third person singular calling them Sumitra and Anees. To be honest, this is my first encounter with this hybrid style. It’s quite effective.

Sumitra and Anees met in “the basement office of Mainstream in Connaught Place, New Delhi”. Their romance blossomed watching “that old staple, a movie … The Householder”. “This, in 1964”, writes Seema, “was a signal to Anees that she would not be averse to get to know him better, in ways not necessarily as ‘just’ friends. It was a test-drive and it worked.”

There’s a beguiling reticence as Seema reveals details of her parents background, life and love story. It makes you yearn for more. “Both Anees and Sumitra were anything but upper class. It was about first-generation migrants with minimal resources trying to pitch their tent in a hot and not very friendly city.”

Finding a place to live seems to have been as difficult in the ’60s as it is for mixed-marriage couples today. On one occasion, after signing the lease, the landlady withdrew because she suddenly realized Anees was not Aneesh.

Seema was born a year later. She admits choosing her name was tricky. “Anees’s mother, on a blue inland, sent an entire list of suggestions … with a Seema tucked-in somewhere. Sumitra leapt at it. She had volunteered to adopt her husband’s surname, happy at the nikah, but for her child, she wanted some ambiguity around how she would be seen … Seema, doubling as both a ‘Hindu’ and a ‘Muslim’ name, seemed perfect.”

Although Seema doesn’t make a lot of it, names bear significant relevance to the Sumitra-Anees story. “‘Anees’ and ‘Sumitra’ mean the same thing. Anees in Arabic and Sumitra in Sanskrit translate as ‘good friends’. It was one more thing that was common to them.”

Half the book is a selection of recipes left by her mother for a daughter who she was convinced could not, would not and had far too little time to cook. They explain the subtitle. But they reveal something more. Her parent’s marriage was “a confluence and khichdi”.

I can’t think of a better description. The first noun suggests a coming together and becoming a single united entity. The second suggests a conscious, deliberate mixture of many different parts to create a new delightful whole.

I don’t know if Sumitra anand Anees fought like Minoo and Shakuntala or followed divergent paths like Vita and Harold. Seema’s story doesn’t go that far. But that’s good. There’s a limit to how much children should reveal of parental discord. A harmonious relationship makes for more pleasing reading. (IANS)

by KARAN THAPAR

by KARAN THAPAR